Meta Description: What is inside a shock absorber? Go beyond the basics. As a leading manufacturer, we reveal the intricate components inside a shock absorber, including pistons, valves, and seals, and explain how they work together for peak performance.

Introduction

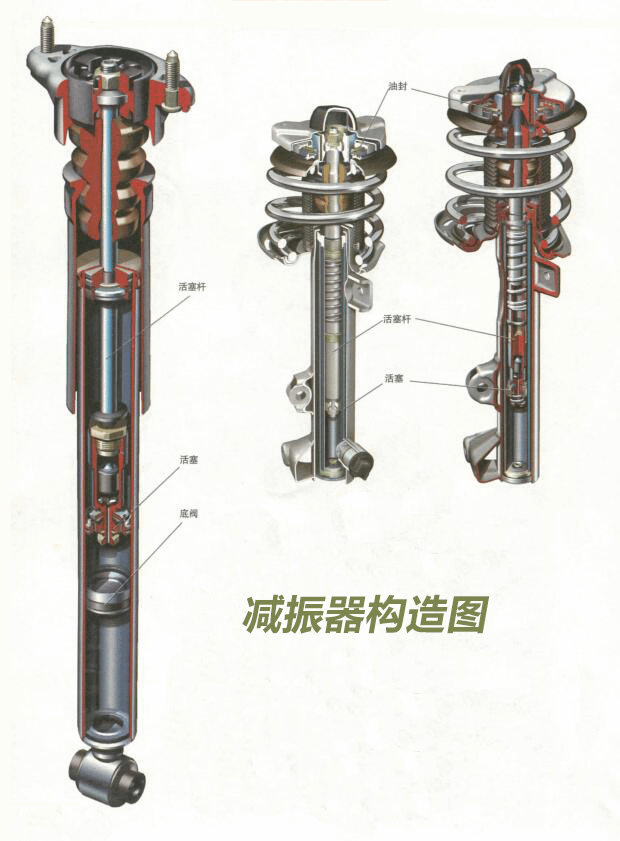

When a driver asks “what is inside a shock absorber?”, they are often looking for a simple answer. However, as a factory that has engineered, machined, and assembled millions of these hydraulic damping devices, we understand that the answer is far more complex and fascinating. A shock absorber is not just a simple metal tube filled with liquid; it is a masterfully designed piece of machinery. Its internal components work in perfect harmony to perform a critical function: controlling the motion of the suspension system. The quality and precision of these shock absorber internals directly determine a vehicle’s ride quality, handling, and, most importantly, safety. This article pulls back the curtain on our manufacturing process to provide an exclusive, factory-level look at what is truly inside a shock absorber.

Core Content

Section 1: The Primary Container: The Pressure and Reserve Tubes

The external shell of a shock absorber, or strut, is the first internal component to consider. The design of this outer shell differs based on the type of shock absorber being manufactured.

1. The Twin-Tube Design: In the most common design for standard passenger vehicles, the shock absorber consists of two tubes.

- Outer Tube (Reserve Tube): Made of a lower-cost, often seamless drawn steel tube, this is the larger, visible shell of the shock absorber.

- Inner Tube (Pressure Tube): This tube is smaller in diameter and slides precisely inside the outer tube. It is typically made from a thicker, higher-grade steel to withstand the internal hydraulic pressures. The entire damping process, where the piston moves through the fluid, occurs inside this inner pressure tube. The space between the inner and outer tubes holds the majority of the hydraulic fluid, acting as a reservoir.

This two-tube architecture is a cost-effective solution, allowing for a larger fluid volume to help manage heat, though it has limitations in high-performance scenarios.

2. The Monotube Design: For high-performance and heavy-duty applications, the design is more sophisticated.

- Single Pressure Tube: A Monotube shock absorber consists of only one, large-diameter pressure tube made from a very strong, seamless steel alloy. This single, robust housing is the key to its performance advantage. It houses the entire assembly, including a floating piston that separates the oil from the high-pressure nitrogen gas charge. This single-chamber design is far more efficient at dissipating heat, making it the preferred choice for racing, trucks, and off-road vehicles where performance fade is a major concern.

Section 2: The Heart of the Device: Piston, Rod, and Valving Assembly

If the tubes are the body, then the piston, piston rod, and valving assembly is the heart of the shock absorber. This is the central assembly that reciprocates inside the pressure tube and performs the actual work of converting motion into heat.

1. Piston Rod: The piston rod is a hardened, precisely polished steel shaft that extends out of the shock absorber‘s body. It connects the main shock absorber assembly to the suspension component, allowing the wheel’s motion to be transferred directly into the unit. Because it is constantly entering and leaving the pressure tube, it must have a flawless, chrome-plated finish to minimize friction and wear on the internal seals.

2. Piston Head and Valving: The piston head, which is attached to the end of the piston rod, is arguably the most complex and precisely engineered component inside a shock absorber. Its entire surface is covered in a series of meticulously calibrated valves (usually referred to as “disc valves” or “stacked disc valves”). These valves are the secret to a shock absorber‘s velocity-sensitive behavior.

- Flow Paths: The piston head features multiple small holes or ports.

- Rebound Valves: When the wheel drops into a pothole and the suspension extends (“rebound”), the piston rod is pulled out of the pressure tube. This creates a low-pressure area behind the piston. To equalize this, fluid must rush from the front of the piston (the side facing the rod mount) to the back. The shock absorber‘s rebound valves are designed to offer significant resistance to this flow, which slows down the suspension’s extension, preventing the tire from bouncing off the road and losing traction. The number, size, and stacking order of these discs are carefully tuned by engineers to deliver a specific “feel” during rebound.

- Compression Valves: When the wheel hits a bump and the suspension compresses, the piston rod is pushed into the pressure tube. This forces fluid from the area behind the piston, through the ports, and to the front. The compression valves offer a lower resistance to this flow than the rebound valves. This allows the suspension to compress relatively easily to absorb a bump, providing a comfortable ride, while still controlling the motion.

The quality of the steel for these discs, their precise flatness, and the torque specifications for the retaining nut that holds them in place are all critical parameters we control on our factory floor. Any variation can lead to inconsistent damping performance.

Section 3: The Lifeblood: Hydraulic Fluid

The hydraulic fluid is not simply ordinary oil; it is a specially formulated hydraulic fluid designed for a specific purpose. Its job is to transfer force from the piston to the valving and, in the case of Monotube shock absorbers to act as a medium for heat transfer.

- Properties: An ideal shock absorber fluid is incompressible, has high-temperature stability (it doesn’t thin out or break down when it gets hot), and has excellent lubricity to minimize wear on the seals and valving components. It also contains additives to inhibit foaming, as air bubbles in the fluid would make it compressible and render the shock absorber useless.

- Quantity and Fill Type: The exact volume and type of fluid are precisely calculated during the engineering phase. In Twin-Tube shock absorbers, the fluid level is typically high enough to submerge all internal components, including the base valve. In Monotube shock absorbers, the fluid fills a portion of the tube below the floating piston.

Section 4: The Critical Barrier: Seals and Gaskets

An shock absorber would be useless if it were to leak fluid or let air in. The system must be completely sealed. Therefore, multiple layers of seals and gaskets are installed at critical points to maintain the hydraulic integrity of the unit.

- Piston Rod Seal: This is the primary seal, located at the top of the pressure tube where the piston rod passes through. It is typically a multi-lip seal designed to contain high hydraulic pressure on the fluid side while wiping any excess fluid off the rod as it retracts. This prevents dirt and grime from being pulled into the pressure tube.

- Pressure Seal: A second, heavy-duty seal is used to completely block the fluid pressure behind the piston, ensuring all fluid is forced through the valving ports as intended.

- Nitrogen Seal (Monotube): In a Monotube shock absorber, there is a critical seal on the floating piston that separates the nitrogen gas charge from the hydraulic oil. This seal must be leak-proof to maintain the high-pressure gas necessary for proper heat dissipation.

- End Cap Gaskets: Gaskets are used where the end caps are welded or pressed onto the pressure tube, providing a final barrier against leaks.

The material science of these elastomeric seals is a key area of our research and development. They must be durable enough to withstand millions of cycles of high-pressure, high-temperature operation without hardening or tearing.

Section 5: Gas Pressurization: The Anti-Fade Solution

Understanding what is inside a shock absorber also means understanding the role of gas. While early shock absorbers were simple hydraulic units, the vast majority produced today are “gas-charged” to combat performance fade.

1. Nitrogen Charge: The gas used is always pure, dry nitrogen. It is not compressed into the fluid itself but is held in a separate chamber.

- Twin-Tube Shock Absorbers: In this design, the gas (around 100-150 psi) is held in the space above the fluid in the reserve tube. This pressurized space serves one main purpose: to prevent the hydraulic fluid from aerating. When a shock heats up, the fluid can foam, creating air bubbles. Since air is compressible, foamy fluid causes the shock absorber to feel “spongy” and lose its ability to dampen motion—a phenomenon known as fade. The nitrogen charge prevents this foaming by keeping the fluid under pressure.

- Monotube Shock Absorbers: The Monotube design takes gas charging to the next level. It uses a much higher-pressure charge (250-400 psi) on the opposite side of a floating piston. This pressurized nitrogen not only prevents aeration but also acts as a massive, pressurized heat sink. As the hydraulic fluid heats up, it expands. The floating piston simply moves, compressing the nitrogen gas. Because gases can store and transfer heat more efficiently than liquids, the nitrogen pulls the heat out of the oil and transfers it to the shock absorber‘s large, outer body, where it can be dissipated into the air.

Conclusion: The Symphony of Components

So, what is inside a shock absorber? As you can see from this factory-level view, it is a symphony of precisely engineered components working in concert. It is a robust outer container (tubes), a powerful reciprocating heart (piston, rod, and valves), the lifeblood that transfers force (hydraulic fluid), the critical seals that maintain integrity (seals and gaskets), and the high-pressure gas charge (nitrogen) that prevents fade. No single component can deliver the performance required for a modern vehicle. It is this precise, integrated engineering—born on a factory floor—that makes the shock absorber an unsung hero of the suspension system. The next time you think about what’s under your car, remember that it’s not a simple tube, but a complex, high-performance machine carefully designed for your safety and comfort.